entagon rethinks bioterror effort

Critics say US$1.5-billion initiative has not delivered results.

Soldiers are yet to see any effective new countermeasures against bioterror agents.K. KULISH/CORBIS

Soldiers are yet to see any effective new countermeasures against bioterror agents.K. KULISH/CORBIS

In the film Contagion, it takes just a few months for scientists to make a vaccine against a deadly virus. Yet a real US military programme that aimed to do just that is being dismantled after five years of trying.

The Transformational Medical Technologies (TMT) initiative, born in the US Department of Defense in 2006, was originally conceived as a five-year, US$1.5-billion project that would substantially accelerate the development of countermeasures to protect soldiers against biological attacks. Made into a permanent programme in 2009, it set out to sequence the genomes of potential bioterror agents, explore new drug technologies and develop 'broad-spectrum' therapies that would work against multiple bacterial and viral pathogens — especially haemorrhagic fever viruses such as Ebola and Marburg. Supporters of the programme point out that three candidate drugs developed under the programme, for pathogens including Ebola virus, are now in clinical trials.

The TMT programme, however, has ceased to exist as a stand-alone effort. Alan Rudolph, director of Chemical and Biological Technologies for the TMT's parent office, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, is folding some TMT projects into other Pentagon efforts and reordering their priorities. Critics say that it has failed in its underlying objective to provide a faster, game-changing approach to biodefence. No antibiotics developed by the TMT have entered clinical trials. The drug candidates it has developed are designed for single pathogens, not multiple threats. And although the programme is set to award a major clinical-trial contract later this year, the drug being tested would treat not exotic, untreatable pathogens but ordinary influenza, a disease already heavily researched outside the Pentagon.

Michael Osterholm of the University of Minnesota's Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy thinks that the programme was overambitious and ill-conceived. "They're wasting tonnes of money," he says.

The programme's architects have vigorously defended its record. "There is a success there that we need to build on," says Jean Reed, who, as deputy assistant to the secretary of defence for chemical and biological defence and chemical demilitarization, laid the plans for the TMT. Now a consultant to the National Defense University in Washington DC, Reed adds that the programme has become the archetype within the defence department for the "development of treatments for biologically engineered and naturally occurring disease threats".

"The TMT from its inception was a high-risk, high-payoff or high-failure effort," says David Hough, who became TMT programme manager in January 2007. He says that the effort has paid off: "If we get an engineered threat or something that we haven't seen before that is causing a lot of deaths, we think we can respond to that." He says that the programme's track record is better than that of the Pentagon's traditional chemical and biological defence research effort over the past decade.

Although the TMT aimed to transform biodefence, it encountered many of the roadblocks that have hindered the nation's biodefence effort as a whole, which has spent $60 billion since 2001 with only modest returns (see Nature 477, 150–152; 2011). Developing broad-spectrum drugs for the battlefield has proved difficult because regulators are more accustomed to evaluating drugs that target one specific disease, and drug companies prefer to focus on diseases that affect many people rather than on obscure pathogens that could serve as bioweapons.

These considerations helped to lead the TMT into focusing on influenza in 2009. That year, US government officials were faced with the double threat of H1N1 swine flu, which threatened to explode into a devastating pandemic, and the more deadly H5N1 bird flu virus, which was continuing to infect small numbers of people.

Government officials were "practically paralysed by the fear that they were dealing with two strains at a time; they didn't know what they were going to do", says Darrell Galloway, Rudolph's predecessor at the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, who was a driving force for the TMT from its inception until he retired in January 2010. Galloway saw influenza as an opening to prove the programme's worth. In May 2009, he awarded a contract to AVI BioPharma of Bothell, Washington, to make a flu drug against the H1N1 virus, using its genetic sequence as a basis. Within months, the company had made a drug and tested it in ferrets.

Yet the move angered some within the Pentagon and perplexed observers, because influenza is the focus of considerable research funded by the US Department of Health and Human Services. "I'm having a really hard time making a connection between the investments we're making and the benefit to soldiers," said one staff member at the Defense Threat Reduction Agency.

The TMT also stumbled because companies attracted to biodefence tend to be small and inexperienced. Larger, established companies prefer to pursue more profitable markets, fearing that the federal government will commit to stockpiling only limited amounts of drugs developed for defence purposes.

The company behind all three TMT drugs now in clinical trials, AVI BioPharma, has never had a drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The company's technology uses antisense, in which short pieces of genetic material bind to a pathogen's genes and block their production. The technology has led to few approved drugs owing to safety problems and a lack of efficacy. Still, the TMT and the Army awarded the company a $291-million, six-year contract last year to fund two clinical trials, for its drugs against Ebola and Marburg viruses. Now AVI BioPharma has set its sights on a contract for clinical trials of its antisense drug for H1N1.

AVI BioPharma's chief executive, Chris Garabedian, says that the company's technology is safer than that tested by other drug firms, and thus can be used in higher doses that are more likely to be effective than other antisense drugs that have failed in the past.

But critics say that it was a mistake for the TMT to invest so much in a technology that does not have a proven track record in infectious disease. "Everybody in that field thinks antisense is a failure, except the [defence department] programme manager," says one biodefence analyst, who did not want to be named.

SOURCE: US DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

SOURCE: US DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

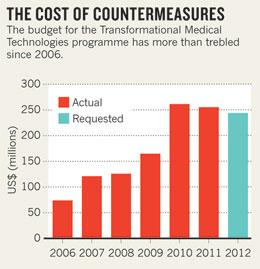

Rudolph, who succeeded Galloway last September, controls the chemical and biological defence research budget, which includes standard drug- and vaccine-research programmes as well as the TMT. Rudolph is combining the TMT research money (see 'The cost of countermeasures') with that for traditional projects, and refocusing on four priorities: surveillance and diagnostics, sensors, countermeasures and decontamination technologies.

Rudolph has retained some TMT projects, such as the pathogen-sequencing studies led by Ian Lipkin of Columbia University in New York, who was a technical adviser on Contagion. But he has cut others, such as a five-year, $24.7-million contract awarded in 2008 to Peregrine Pharmaceuticals of Tustin, California, to find antibodies against haemorrhagic fevers. The TMT funding for AVI BioPharma's two clinical trials will continue, however, as the trials are managed separately by Hough.

Whether the dismantling of the TMT will improve the Pentagon's biodefence success rate remains to be seen, says Tom Inglesby at the Center for Biosecurity of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Baltimore, Maryland. "In the end, the question will be, 'Did Rudolph make progress in the time he was there with the money that he had?' Ultimately, he will be held accountable."

Comments

If you find something abusive or inappropriate or which does not otherwise comply with our Terms or Community Guidelines, please select the relevant'Report this comment' link.

Comments on this thread are vetted after posting.

The author also seems to be confused with two concepts: One where an emergency (Such as in Contagion) causes the government to bypass normal standards and rush a drug to production in order to stave off disaster. The other, is what we currently have: An agency helping along a technology through the long, expensive process of development before an emergency hits. So, contrary to the lede of the story, TMT has not spent 5 years and failed to produce a treatment for a deadly virus. In fact, it took much less time than "a few months" like in Contagion. The drugs for Ebola, Marburg and now influenza all were created by Avi-biopharma in a matter of days and are now being tested for safety. Avi-biopharma has also created several other drugs using the same technology during rapid-response exercises, all of which could conceivably be used in an emergency, but will need funding in order to go to clinical trials.